Trailblazers and latecomers: open banking around the world

Last editedMay 20226 min read

With the ongoing buzz and media focus, ‘open banking’ is likely a term you’re already familiar with.

In case you’re not, it describes the process of banks and other financial institutions enabling customers to share their financial data with trusted providers (through the use of open banking APIs). Open banking makes bank-to-bank payments much quicker and easier, and allows customers to see their financial data in one place. Many fintechs - including GoCardless - and other financial services providers see it as the development that will shape the future of payments.

If you’re looking for an easy-to-understand introduction to open banking, start with this useful guide.

But even with some knowledge, it can be difficult to fully understand what open banking means for your business and your customers. And when you add the vastly different levels of open banking maturity and differing approaches between countries, the picture is further muddled.

This guide will explain how advanced open banking models are in several major markets, as well as key terminology, and where each country is headed on its open banking journey.

A brief history of open banking around the world

Open banking first sprang into existence in July 2013 as part of the European Commission’s revised PSD2 proposal, in which it recommended that banks allow third parties to access account data and initiate payments. These recommendations essentially created the foundation of open banking.

Fast forward to 2021, and open banking is a truly global initiative. At least 87% of countries have some form of Open API. In Europe alone, there are at least 410 Third-Party Providers (TPPs) - online services providers authorized to access data using open banking frameworks.

But which countries are leading the way, and which are yet to really harness the potential of open banking?

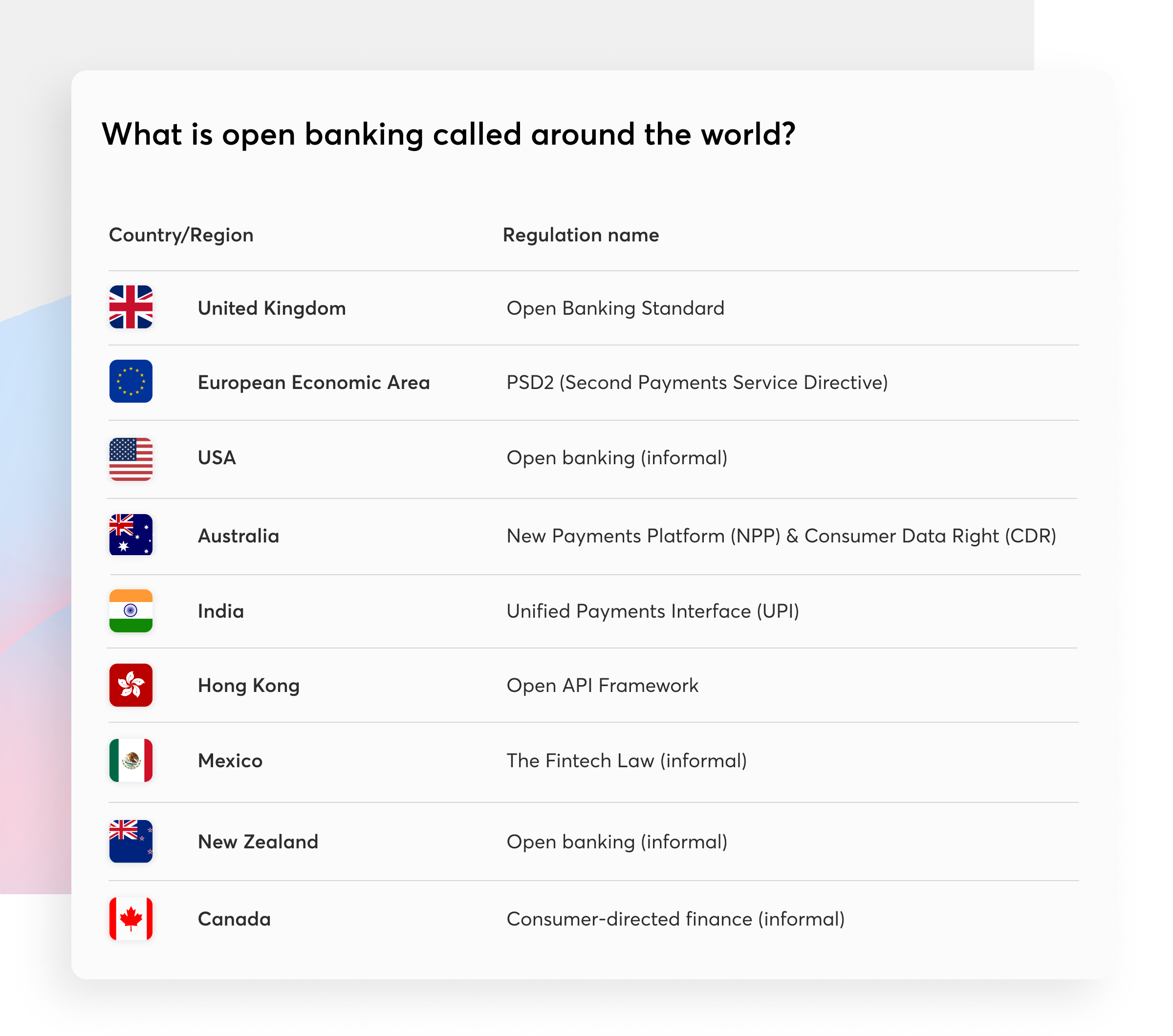

Key terminology differences

While ‘open banking’ (lower-case) is used as a generic term for a set of regulations and initiatives around the world, different countries have different names for their open banking systems. This is particularly true for countries where open banking is being driven by government regulation:

United Kingdom

The state of open banking in the UK

Open banking legislation in the UK required the nine biggest UK banks - HSBC, Barclays, RBS, Santander, Bank of Ireland, Allied Irish Bank, Danske, Lloyds, and Nationwide - to create open APIs that allow Third-Party Providers (TPPs) to access customer account data and payment services in a secure and standardized form.

The deadline to have these APIs ready was January 2018. While only the above nine banks were legally required to create open APIs, more voluntarily followed suit, including Revolut, Metro Bank, Tide, and many others.

In the UK, there are two ways TPPs can make use of open banking APIs. TPPs can be Account Information Service Providers (AISPs), which allows them to instantly connect payer information and data with a business, including balance information and verification. They can also be Payment Initiation Service Providers (PISPs), which enables them to make instant bank-to-bank payments without the need for a card, manual bank transfer, or Direct Debit mandate.

Since 2018, the Open Banking Implementation Entity has published and expanded the Open Banking Standard, designed to help account providers meet API requirements.

It’s fair to say that the UK is one of the countries leading the way in open banking, innovation, and consumer uptake. According to Open Banking’s December 2020 update, there are now 294 regulated providers of open banking in the UK (215 TPPs and 79 account providers).

As of January 2021, more than 2.5 million UK consumers have used open banking-enabled products.

The future of open banking in the UK

Despite the strong growth of open banking product usage in the UK, only 102 of the 294 regulated providers have a live customer offering, so it’s reasonable to expect increased uptake as more providers roll out new and innovative products.

Research from Tink showed that key stakeholders in UK financial institutions have some of the most positive attitudes towards open banking. 68% agree that open banking is viewed as an opportunity in their organization, while 70% have a clear strategy to realize the potential of open banking.

Despite this positivity, consumers remain suspicious of open banking. According to ING research, only 23% of UK consumers are happy for their financial information to be shared using the open banking model. The question is whether these attitudes impact consumer behavior.

PWC research indicates that 64% of adults will be ‘adopters’ of open banking by 2022.

Six reasons why you can’t ignore payments powered by open banking

The European Economic Area (EEA)

The state of open banking in Europe

While there will be some key differences in individual countries in the EEA, the group, as a whole, is moving steadily towards having a usable open banking infrastructure.

But while the European Commission made its initial PSD2 recommendations in 2013, and the deadline for PSD2 readiness was 2018 (as was the case in the UK), relevant APIs from Europe are about 12-18 months behind their UK counterparts. With this, Europe is in danger of being seen, on the global stage, as a laggard.

Like the UK, TPPs in the EEA will be able to make use of open banking as an AISP or PISP (or both).

The future of open banking in Europe

As European open banking APIs are 12-18 months behind UK APIs, we can expect to see a similar trajectory for the growth of TPPs using open banking to power new products as we’ve seen in the UK across 2020. While not quite as positive as the UK, 58% of European fintech decision-makers still see open banking as an opportunity.

GoCardless Senior Product Manager, Michael Bridgeman, speculates we’ll see a shift from a central regulatory body to something on a national level: “The EBA kicked off open banking in Europe, and they will come down hard on countries not doing their part to develop it. But we're also seeing the challenges of trying to coordinate 27 countries, so the EBA may also devolve some responsibilities, as we saw with Strong Customer Authentication exemptions a year or two ago."

USA

The state of open banking in the US

Unlike the UK and Europe, the US has taken an industry-led approach to open banking. This means the industry is effectively building itself with little-to-no oversight from governing bodies.

An early frontrunner in the industry is Plaid, which uses a data transfer network to power fintech and finance products. Visa announced it was acquiring Plaid for over $5 billion in early 2020, but the deal was called off after the takeover was blocked by the US Department of Justice.

Currently, open banking in the US has been limited to account information products, which is effectively done by screen scraping. Screen scraping is the automated use of a website to impersonate a web browser, to extract data or perform actions that users would usually perform manually on the website. As data collected from screen scraping needs to be stored unencrypted (or at least be accessible in an unencrypted form to those doing the scraping), sensitive information could easily be leaked.

The future of open banking in the USA

While the US definitely lags behind the UK and Europe in terms of open banking technology and customer understanding, there is still increasing demand for products like Plaid (accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic). According to Plaid, its customer base has increased by 60% in 2020.

As the rest of the world’s open banking efforts gather pace, global companies headquartered in the US will start to benefit from open banking in their international operations. This will likely lead to businesses beginning to demand more from the US itself.

Australia

The state of open banking in Australia

Australia’s open banking efforts, like the UK and Europe, have been regulation-led, but the rate of change has been much slower.

Despite announcing the New Payments Platform (NPP) - a collaborative effort between 13 of Australia’s biggest banks to create a set of guidelines for faster, frictionless bank-to-bank payments - in July 2013, it only launched in late 2020.

In addition to the NPP, the Consumer Data Right (CDR) legislation gives consumers more rights over their own data, including the right to share it with trusted third parties. Right now, it’s only available to a very small set of accredited businesses. This is down to a complex accreditation process and CDR framework.

The future of open banking in Australia

Despite moving slower than some other major markets, it’s clear that Australia’s regulatory bodies see open banking as a key framework for the future of banking and finance in Australia.

One key service in the works by the NPP is the Mandated Payments Service (MPS), which will allow consumers to authorize third parties to initiate payments from their bank accounts instantly. The NPP plans to enable third-party payment initiation for MPS by the end of 2021, and support international payments by the end of 2022.

The MPS is the most exciting part of the NPP, and open banking in general in Australia, because of its advantages over existing payment options, and the wider range of use cases it can address. Its always-on, instant nature means it vastly improves on the three-day waiting time for BECS bank-to-bank payments. It could also lead to consumers and businesses becoming less reliant on credit cards.

With the MPS we could see consumers link up to apps like Uber or Netflix to make subscription payments, while utility companies could pull regular payments from a customer more dependably, and likely at a lower cost.

Other notable open banking innovators

New Zealand

So far, New Zealand has taken a much more hands-off approach to open banking than its nearest major neighbor, Australia. There has been discussion of a Consumer Data Rights (CDR) similar to Australia’s, but nothing has been finalized.

Canada

Canada, like the US, has so far taken an industry-led approach to open banking. However, there are government-led consultations looking at how to create more regulatory oversight for the future. A 2019 report recommends that the implementation of a structured framework would address consumer privacy concerns. The report also recommended that open banking in Canada be referred to as ‘consumer-directed finance’.

India

Open banking is already well established in India, stemming from the launch of the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in 2016. UPI allows consumers to access bank accounts via registered apps, and make transactions to other banks. India is seen as having a hybrid approach, partly driven by the market and partly by regulation.

Hong Kong

The Open API framework was announced by Hong Kong back in September 2017, as part of a wider plan to move into the era of ‘smart banking’. The framework was officially published in 2018. By May 2020, more than 50% of incumbent banks had either open APIs or other open banking innovations.

Mexico

In March of 2020, Banco de Mexico published its first rules for open banking. Mexico is seen as a fintech leader in Latin America, with at least 394 companies offering technology-powered financial services, so regulators are keen to harness the open banking model.

What should your business do right now?

While open banking is still developing around the world, with some countries at the forefront of the model and others lagging behind, it will continue to shape the global fintech industry for a long time. You’ll soon begin to see several benefits in your payment operations.

Open banking-powered innovations in the payment sector will lead to:

Fraud prevention

Payment-related cost savings

To find out more about why open banking will become more and more important for enterprises and scaling businesses, read our guide.